Does the ideal voice user interface seem human?

The metaphors in place for accessing information through graphic user interfaces, (GUIs) are clear: cursors touch, folders contain, hyperlinks redirect. Stylistic attributes of these tools have evolved, but their functionality remains consistent.

Voice user interfaces, (VUIs) do not make use of the metaphors we are acquainted with. Instead of a predictable system of clickable containers and doorways, they introduce helpful disembodied voices. New users don’t learn their capabilities by clicking around and exploring, but rather by cautiously mimicking behaviors witnessed in advertisements and other homes.

Sometimes VUIs get it right and users find just what they are looking for: the weather forecast, an organized list, a reminder, a favorite song, or an obscure fact. But, are convenience and recreation really the most meaningful use for non-visual technologies? Does conversational interaction limit VUI utility?

Scoping the problem

Unpredictable Timing + accuracy

Without visual technology, users might be adept at conversing with disembodied voices. But, screens abound. Every time an individual elects to use a VUI for an unfamiliar task, she forgoes the certainty of a predictable device. Some of a user’s cognitive energy, before and after articulating a command, is devoted to measuring the VUI’s speed and functionality relative to that of the familiar GUI in their pocket or on their desk.

inconsistent Mental Model

Most users do not actually believe that their devices are conscious. But, they do think of them as such. If one were to think of a VUI as a sea of ones and zeros or a mechanical instrument, speaking to it would be counterintuitive. We think of VUIs as conscious entities because in order to use them we must treat them like conscious entities.

But, what type of conscious entities exactly are they ? Sometimes the content VUIs deliver seems to originate from a human and sometimes it seems to originate from a computer with a human voice. It’s difficult to bond with a VUI the way a child might a stuffed animal, action, figure or doll because it's difficult maintain a clear vision of what exactly it is.

Scoping the opportunity

Ultimately, the purpose of the VUI, is not to simulate a human, but to function as a portal to ideas and applications. By prioritizing the human relationship to information— considering context, hierarchy, and navigability, VUI designers stand to revolutionize the way we search for and explore digital content.

visualization/ Final Deliverables

Speed

Scenario: Jane opens and explores a saved document containing her biology reading assignment. She uses a scroll wheel to scan and navigate the content- speeding past information, adjusting her position, and changing the verbosity of each sentence

Signifiers

Scenario: Alex searches through her emails from Paul. She is looking for a particular message. Sound cues help Alex anticipate the information she is about to encounter. Lists are prefaced by a succession of staccato sounds corresponding to list length. Bodies of text are preceded by melodies.

Navigation

Scenario: Alan comes across an intriguing artist while reading the Sunday times. He falls into a Wikipedia rabbit hole by looking up his name. Sound cues identify hyperlinks within webpages. Alan uses monosyllabic utterances and commands to select, interrupt, and pause the text.

Research Process

Possibilities and capabilities

Audio Material Palette

Restricting communication to a limited palette results in a surprising constellation of sounds.

Google materials has proposed a visual language for application design that honors the physics of paper in space. Designers who adhere to this code are able to design interfaces that are not only stylized and aesthetically pleasing, but expected and understandable. Noticing that an alarm clock buzzer, a song, and the "woosh!" of an email delivery each reference a different imagined space, I questioned if one might standardize sound around a single material.

Method

In this experiment I set out to exhaust the range of sounds one can produce with paper. My actions ranged from meaningful operations (like crumpling, cutting, and taping paper) to abstract movements more sensitive to the physical properties of paper (like sweeping the table with it or dropping it on an edge.)

observations

While not every action produced a recognizable or seemingly related sound, every sound was believable as something that had occurred in physical space.

The variability of the volume produced by certain actions seemed to eclipse some of the more subtle changes in sound.

Mouth Clicks

A range of non-speech vocalizations and facial movements have not yet been exploited by interaction design.

What is the spoken equivalent of a mouse click? How can we produce quick, loud sounds, with low cognitive load. How might one interrupt spoken content? Can we produce vocal sounds without inhaling?

Method

I asked three individuals to produce as many monosyllabic non-speech sounds as they could think of.

observations

Participants often lost sight of which sounds they had previously made.

Sounds compared to noises used by humans to attempt communication with animals,

When unsure of what to do next participants defaulted to changing the positioning of their jaw and mouth.

Auditory Charades

We do not yet have a standardized language for communicating content with sound, we are much accustomed to gesture and mime.

Can sound contain meaning as icons do? It is common for sound effects to accompany motion in video games and puppet shows, for music to deliver emotional context during movies, for alarms and notification sounds to signify an event. But, can nonspeech sound contain meaning as words do?

Method

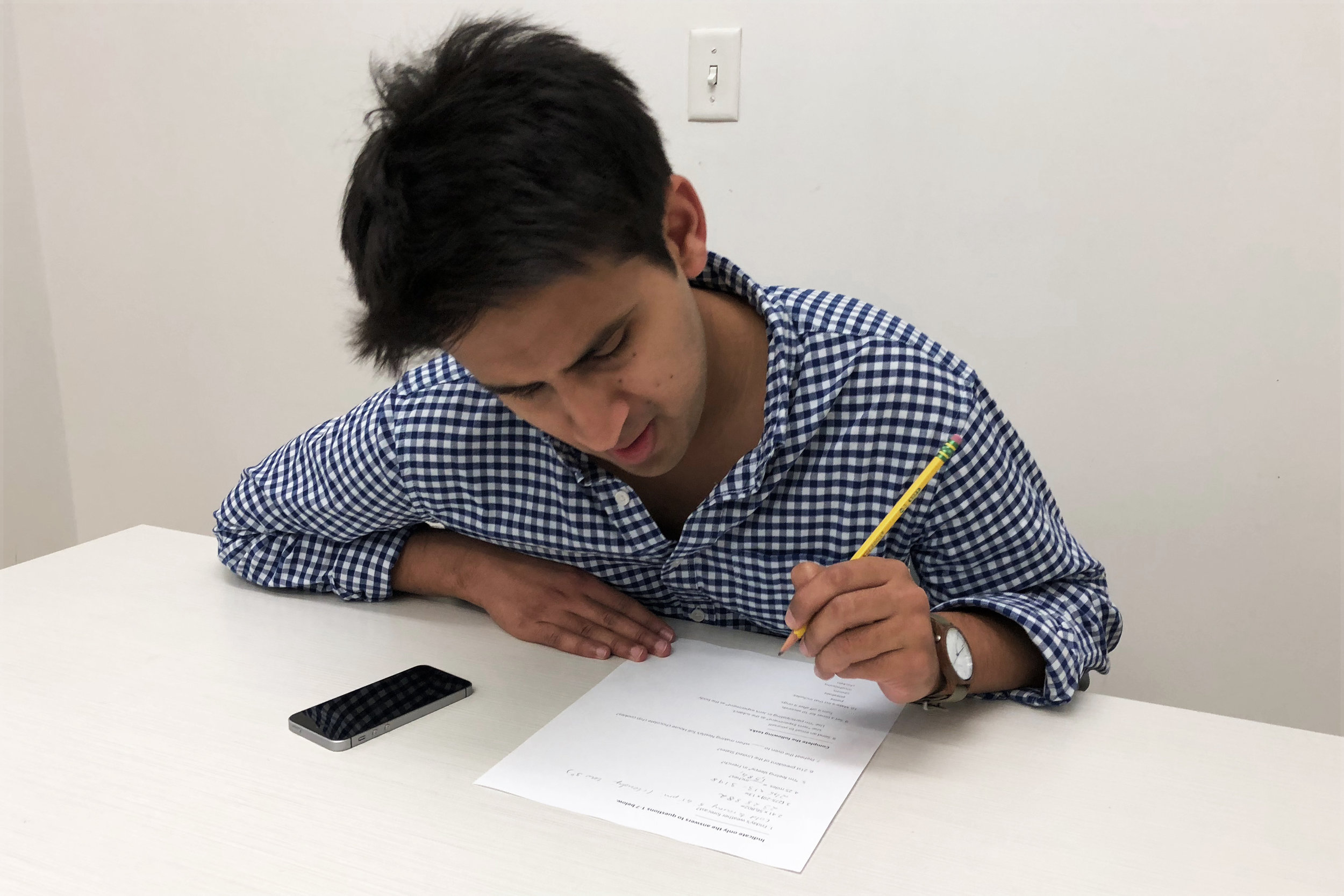

During this challenge i instructed to participants to use only the table surface before them and their own hands to create sounds representing the nouns, adjectives, and verbs (handed to them on postit notes.)

Observations

Participants’ sound-making strategies varied greatly.

Sometimes they anthropomorphized their fingers.

Sometimes they used symbolic gestures.

Sometimes they sought to create feelings associated with words.

Sometimes they sought to mime events associated with words.

Filtering text with sentence diagrams

Ideas can be distilled into short groupings of words that carry meaning even though they don’t sound like conventional language.

A sentence diagram is a pictorial representation of the grammatical structure of a sentence. Sentence diagrams help readers to parse out key words that capture the meaning of a sentence. These words (subject, verb, and direct object) are scribed on the horizontal while supporting descriptive and connective words are scribed on the diagonal.

Method

I created sentence diagrams for the first chapter of a popular novel to effectuate the incremental filtration of nonessential words from this text.

observations

The essence of each sentence remained in tact until I removed the direct object.

When negative descriptive words such as never, seldom, and not were featured in sentences, filtering away these words confused the meaning of the sentence.

Audio Abstractions

When communication is restricted to abstract sounds feedback loops are accelerated and engagement is sustained.

I was curious about how the students might respond to a VUI that communicated with sound rather than language.

Method

I introduced students to “Mo,” a prop VUI concealing a blue-tooth speaker. Students were told that Mo is not as smart as Alexa and can only respond to yes or no questions.

observations

Almost all of the students eventually concluded that the slightly lower pitch sounds meant no.

Many students assumed that they needed to activate Mo with a wake word.

Human Command Line

The ability to perform visual tasks in parallel with a voice controlled interface can create a more integrated workflow.

Command lines and search bars eliminate the need to spatially locate digital tools. In some cases this facilitates work in design environments that feature many options. However, the command line requires the designer to relocate his or her eyes from the work they are engaged in to the the text entry space. I was curious about whether a vocal command line might eliminate this oscillation thereby creating a more fluid modeling experience.

Method

Two participants with advanced working knowledge of Rhino shared screens, one in charge of typing tool names into the command line the other responsible for making all design decisions and calling out the tool names.

observations

This dynamic works well for typing tools into the command line. But, it is less helpful for keyboard qualifiers that need to be held down in conjunction with mouse clicks i.e. option and shift.

The modeling participant’s glance stayed fixed on his work for the extent of the experiment

The modeling participant felt that his experience more closely related to the the act of building a model in physical space.

responses to current vui design

VUI Obstacle Course

Observing strict conversational formalities when interacting with voice user interfaces creates unnecessary obstacles in accessing information.

Method

During this obstacle course, participants used the VUIs on their own phones to answer questions and complete tasks. Four of my participants owned iPhones and used Siri. Two of my participants owned androids and used Google Assistant.

observations

Siri uses sound effects to indicate the metaphorical movement of a microphone between user and virtual assistant. Due to poor wifi and participant hesitation these sound effects often occurred at unexpected moments.

Siri users did not realize that it was unnecessary to say “Hey Siri” after the “i’m listening” sound had played.

Periods of silence seemed to suggest that the VUI was thinking when it had simply not heard the question asked.

Participants often second guessed the phrasing of their questions after beginning to ask them.

Troubleshooting Alexa

The existing conversational models for voice user interfaces often result in user confusion and disengagement .

Method

During this experiment I challenged 5th grade students to ask Alexa, who the oldest person in the world is, where they live, and what their age is. While this seems like a fairly straightforward line of inquiry, it is not.

observations

Students were reluctant to interrupt Alexa. Only after numerous identical wrong answers did students cut her off.

When students felt most engaged in the conversation they often forgot to use the wake word (Alexa.)

Students seemed unsure of where to look while listening, often staring into my face, or out the window.

present behaviors

Affording interruption

During a chat, we can generally anticipate when we are going to be interrupted by looking at a friend's facial expressions and gesture. But what about when we can't see the other party?

Interruption is a valuable tool in conversation. It communicates that a participant is engaged, eager, and autonomous. It also always a participant to put the breaks on an irrelevant topic or force the exchange into a domain relevant to their immediate interests.

Method

During the above pictured experiment two individuals communicate through a blockade. Neither is able to see the facial expression or gesture of the other. Further the two participants have been instructed to speak at a slower pace than usual.

Void Filler

Nonverbal vocalizations allow us to augment the flow of communicated information.

How does non-speech sound inform casual conversation? What are the subtle cues that help us to understand the needs of those we communicate with?

Method

Study 5 minute conversations between pairs of people.

observations

I noticed that laughter functioned as a fail proof silence filler, and a means of communicating attention, encouragement, and approval.

In some cases, repeated bouts of laughter from the same individual seemed to suggest a performer/spectator dynamic.

In some cases laughter served as a respectful way to break the stress of eye contact.

I also noticed that explicit turn taking was absent from most conversations.

Strong agreement was often expressed when one party spoke simultaneous to the other party saying things like “right right right” or “yes.”

Words like “um” “uh” “erm” “ah” proved elastic. While generally speakers seemed to use them to say “i’m thinking “ the melody that carried this sound and sentiment varied drastically. Based on how prepared they were to respond.